TL;DR

Between mid-December and late January, four npm accounts massively abused the npm registry by publishing over 100 packages with thousands of versions each, embedding large volumes of encrypted or compressed data disguised as WOFF2 font files. While individual packages appeared innocuous and contained no malicious code, the operation resulted in approximately 34 TiB of uploaded data and an estimated 4.3 PiB transferred via downloads in a single month. Analysis shows the files were not real fonts but data chunks, with some package versions revealing HLS playlists pointing to hundreds of encrypted media segments, suggesting the registry was misused as a large-scale content distribution mechanism.

Although the incident posed no direct security risk to developers or end users, it represents a severe strain on npm’s shared infrastructure and a likely violation of its acceptable use policy. The accounts involved have since been removed, but the episode highlights a broader systemic issue: critical open-source infrastructure such as npm and PyPI operates at massive scale with limited resources and depends on responsible usage and community support. This case underscores growing concerns from infrastructure maintainers that unchecked abuse—rather than malware—can threaten the sustainability and reliability of the open-source ecosystem.

What Happened

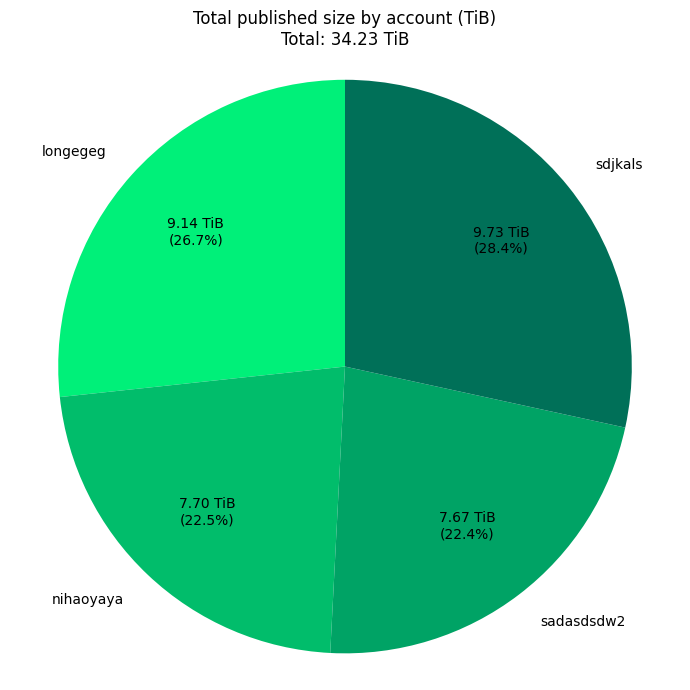

Starting December 12, four different npm accounts started to flood npm with dozens of packages, each having thousands of versions. They contain megabytes of binary data disguised as WOFF2 fonts, amounting to a total of 34 TiB.

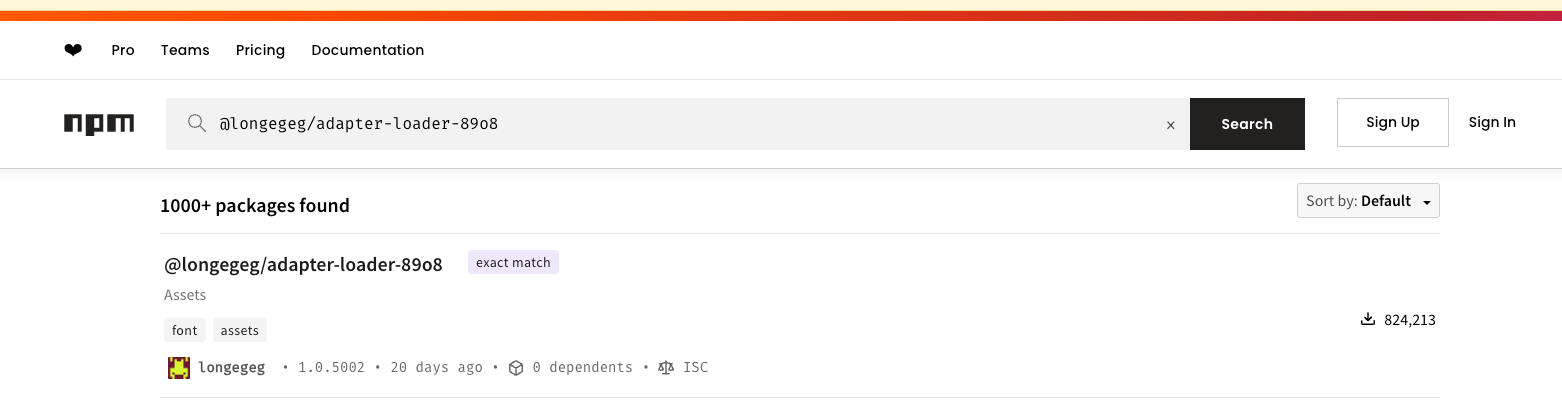

The packages from user longegeg have already been reported in a blog post from Dec 16, however, the presence of three other accounts, as well as the continued publishing and download activity throughout December and January, reveals the scale of this operation.

On December 13, just one day after the first packages appeared on npm, two of four accounts were added to a deny list in order to prevent the packages from being mirrored to https://registry.npmmirror.com.

On January 22, a bit more than one month after the first package publications, download numbers shown on npm go into the hundreds of thousands (see screenshot of one example package).

The table below illustrates the true scale of this operation, showing their package names, the number of published versions, the total size of all package versions taken together, their average size, the monthly download numbers as well as the overall data size transferred (full CSV available for download).

In total, considering the downloads of all 101 packages, a staggering 4.3 PiB went over the wire during the last month.

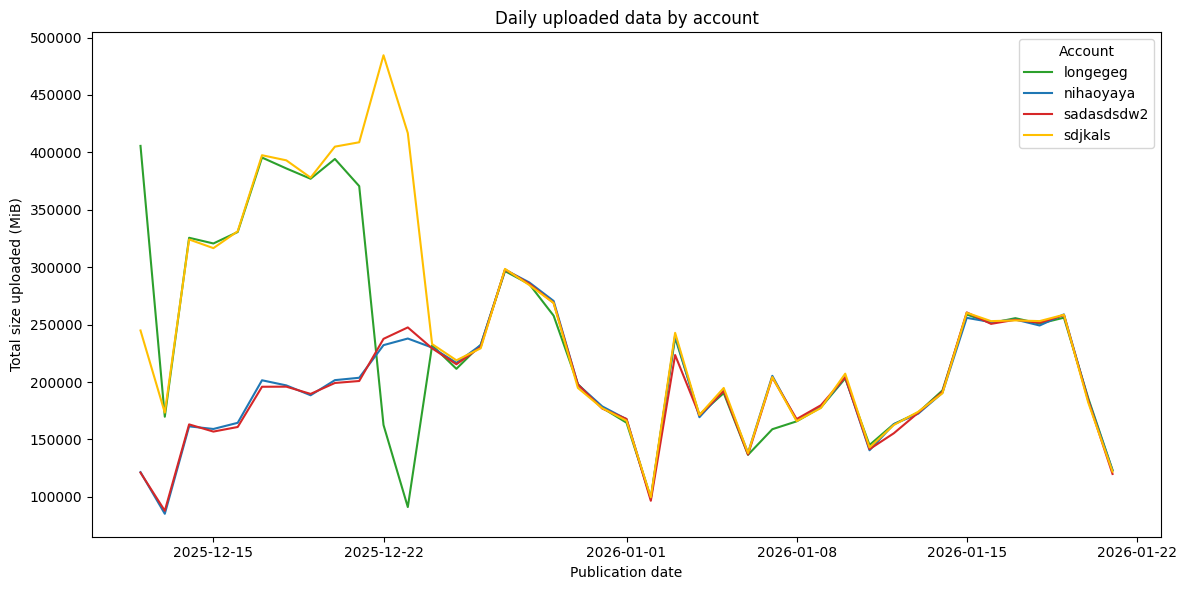

Analyzing the upload behavior of the individual accounts reveals an interesting pattern: The graph below shows the aggregated data upload per day and account. Starting around Christmas, all of the four accounts uploaded almost identical amounts of data per day, split across their packages and versions.

We did reach out to what appear to be throw-away Gmail and Outlook email addresses, but have not received any comments on the nature of those packages and their content.

Meanwhile, on January 23, all of the four accounts have been deleted from npm itself. The packages cannot be found on npmjs.com anymore, and the npm API shows them as “unpublished”. For the time being, the tarball download URLs continue to work – and can be reconstructed from the CSV attached to this blog post.

Technical Analysis

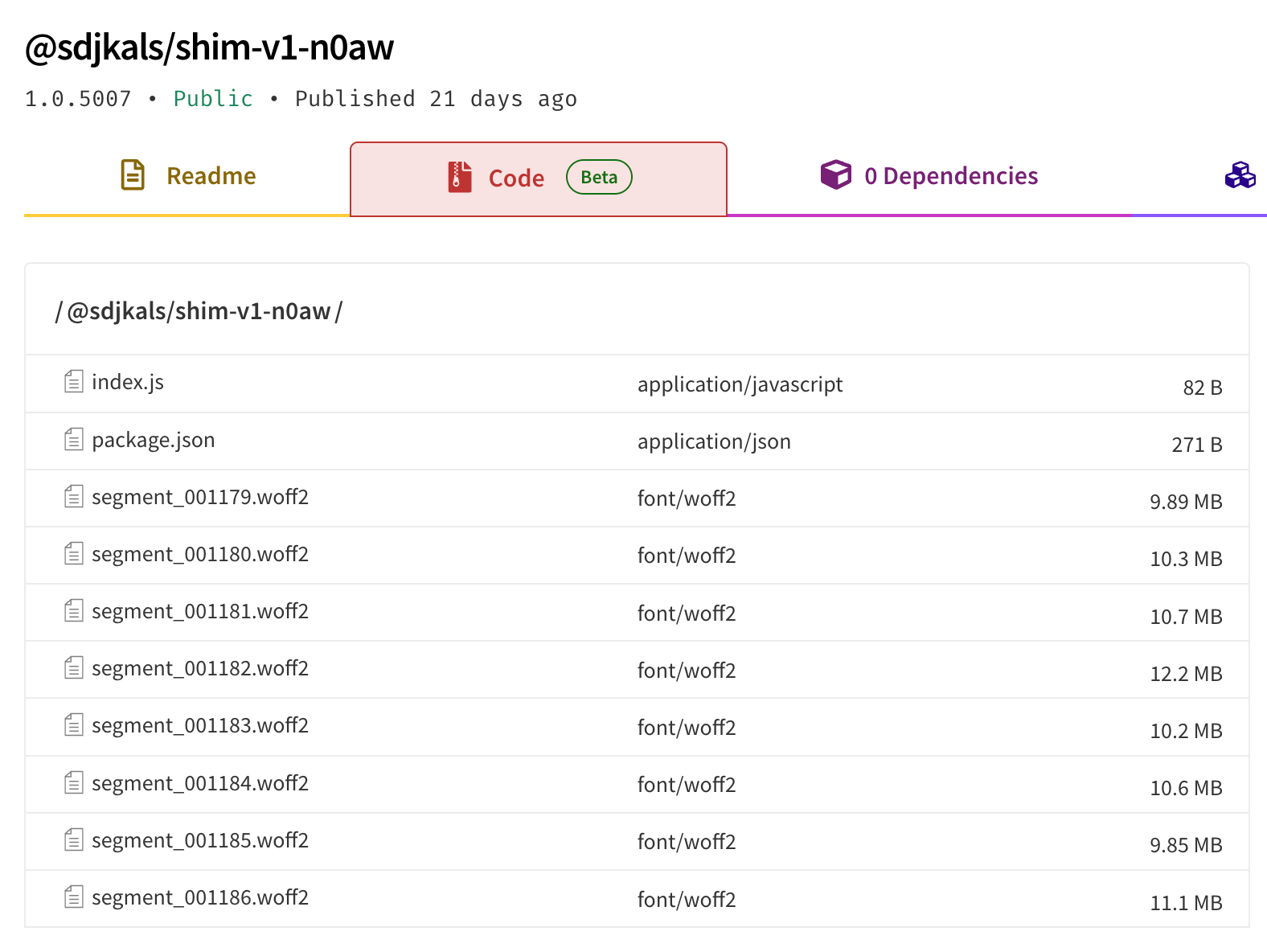

Zooming in on the packages’ content, the vast majority of tarballs follow the same structure (see screenshot): They contain a minimalistic package.json – without any installation hooks or meaningful metadata, and a small index.js, which exports a tiny config object for a custom font. Those two files are almost identical across all the packages from all four accounts.

Other than that, they contain dozens of segment_<6-digit index>.woff2 files with varying sizes up to 12MB. They appear to be font files at first sight, and begin with a valid WOFF2 magic header (wOF2).

However, they claim a total file length of 1.5 GB in their header, which is wildly inconsistent with the actual file sizes. Multiple segment files share identical headers but different contents, and an analysis with binwalk indicates that the bytes look uniformly random, which is typical of compressed or encrypted data, not structured font data.

All of this is consistent with data chunks masquerading as fonts rather than real, standalone fonts. As such, it does not come by surprise that the files cannot be processed by fonttools, a prominent Python package with WOFF2 support.

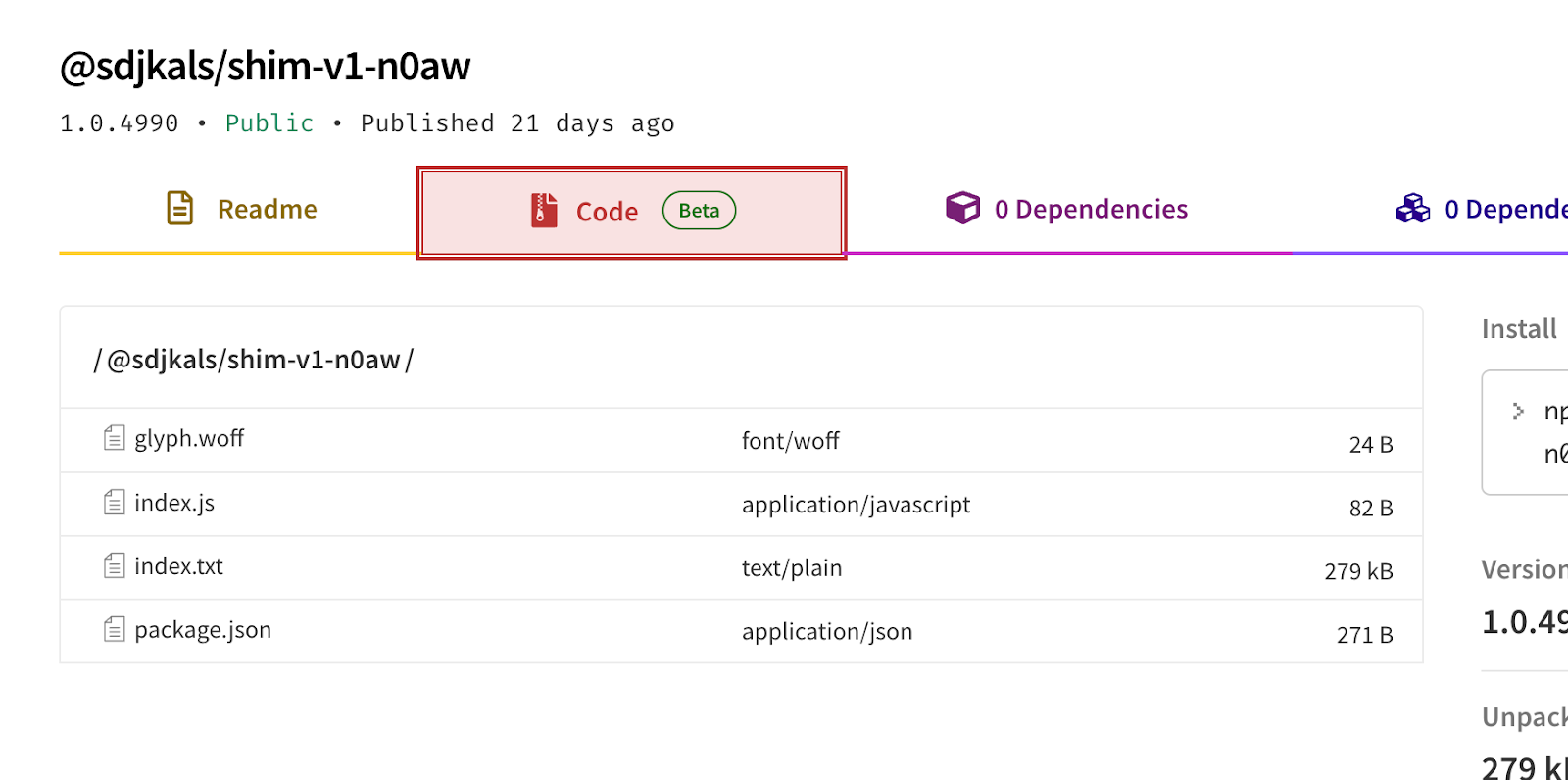

However, among the thousands of package versions containing WOFF2 files, there are a few, e.g., @sdjkals/shim-v1-n0aw v1.0.4990, which are much smaller and comprise an index.txt file and a glyph.woff (see screenshot).

The index.txt file, once stripped from its nonsensical “wOF2” header, turns out to be an HLS media playlist that references glyph.woff as AES key, and points to individual segments – supposedly contained in other versions of the same package.

#EXTM3U

#EXT-X-VERSION:3

#EXT-X-TARGETDURATION:6

#EXT-X-MEDIA-SEQUENCE:0

#EXT-X-KEY:METHOD=AES-128,URI="/cdn/assets/deliveries/v2/m_xD2jhZxtu-tnOPNJRXzoYjhDJWS0Iw-B0RxR-50bJ7VLbWV-vF0NbzjZFsdB1imXUuN-S4O-Trw7m70EYmLV8JKUxwKjtb3Wuac-Nq5JpepfLxvMLOslQ/glyph.woff?t=8ca5f28a0c&e=2082670575",IV=0x93aa8e18f089a1919fdf8a62777172ef

#EXTINF:6.000000,

/cdn/assets/deliveries/v2/Xuk_Mi9AvJCoKZH7STzNoTN5a40-btwvdoWG36N6d2n4tYOBY9kREGWZwiShOC2i_ybvLY_AuDzcox6RLnqF_0_qwBUS0ihRYPXCfPrpeQtQBvp1kdzDPjy94r_sbp51l3H8ofk/seg-0.woff2?t=4a2dedb94b&e=2082670575

#EXTINF:6.000000,

/cdn/assets/deliveries/v2/0aN8X__EGQobRZWru0CEIhZBdojrAI7yHCaqb2wttlK5YmfPJ0NJqGNHv7oa8vKu8QkYg0f6z3BLmjWubxQgrrtggvZcB8gIwnUNhhqLngbpiVFegn9RUgTDMn3ERVAupEIb34E/seg-1.woff2?t=21bf183e9b&e=2082670575

<many more references>

#EXTINF:6.000000,

/cdn/assets/deliveries/v2/nkHwjM527zu3Qj4ceYdZQFmXyGqv5Q7PLkGuy6fyvGdZTPgxiOTVmxWElbZgeX2c2FKtSihX8CBgP1ckmRlOyZYGRaOP9slVFFH6WvVZ6dNpaKXMQdqqEHcl92bHhPQPLtLyzttF/seg-1245.woff2?t=7c75b7f9a6&e=2082670575

#EXTINF:6.000000,

/cdn/assets/deliveries/v2/bA8-I1cESbVkH3dwPSVqXgprYYb0AeKhmKWG_wcR9UubODBsC5JxRPGX1A9hjkDEjA4SgQEZx2dLxMjoooXl5tdc2raD56-pl01Wxu_cslMjX91ScmwQcMmgsL0W_bz91IYlKtj_/seg-1246.woff2?t=8c938137ec&e=2082670575

#EXT-X-ENDLISTIn this example, there are 1247 snippets of 6 seconds length, summing up to a total of 125 minutes of audio or, more probably, considering the significant file size per segment, video material.

Impact

The packages do not contain any malicious code – in fact, they contain hardly any code at all. In other words, installing those packages does not have any detrimental impact on developer machines. No malicious code is triggered during installation or at later points in time. As such, without any obvious malicious intent, the packages cannot be classified as malware or supply chain attacks.

However, the publication and download of humongous amounts of data in such a short time frame looks like a strong abuse of npm’s shared infrastructure resources, in violation of npm Open-Source terms. Specifically, point 17 of the acceptable use policy demands users to “not strain the infrastructure of npm Services with an unreasonable volume of requests, or requests designed to impose an unreasonable load on IT systems underlying npm Services”.

It remains to be seen whether the encrypted data is also in violation of the acceptable use policy – esp. considering the effort made to conceal the actual content as font data.

As such, the main impact is not on end users and developers, but on the providers of shared infrastructures underpinning our open source ecosystems.

This observation resonates very well with a joint statement from organizations operating public open source infrastructure, published September 2025: Package registries such as Python Package Index (PyPI) and npm enable billions of dependency downloads each year and serve as critical distribution channels for both open source and commercial software.

Despite their central role, these platforms are typically operated by non-profit organizations or small teams, often with significant reliance on volunteers, donations, and sponsorships. Their mission is to serve the entire open source community fairly and reliably. However, this model assumes broadly responsible use of shared resources.

“Yet, across ecosystems, most organizations that benefit from these services do not contribute financially, leaving a small group of stewards to carry the burden.”

References

- Open Infrastructure is Not Free: A Joint Statement on Sustainable Stewardship (OpenSSF, Sep 23, 2025)

- NPM User Flooding Registry with Fake Font Packages (Mend, Dec 16, 2025)

- npm Registry Flooded with 748 Movie-Storing Packages (Sonatype, Jan 25, 2024)

Detect and block malware

What's next?

When you're ready to take the next step in securing your software supply chain, here are 3 ways Endor Labs can help:

.avif)