Security researcher Paul McCarty recently uncovered a coordinated spam campaign in npm. The IndonesianFoods worm, as it has been named, consists of over 43,000 spam packages containing dormant payloads published across at least 11 user accounts (and counting), starting from two years ago. The packages were systematically published over an extended period, flooding the npm registry with junk packages that survived in the ecosystem for almost two years.

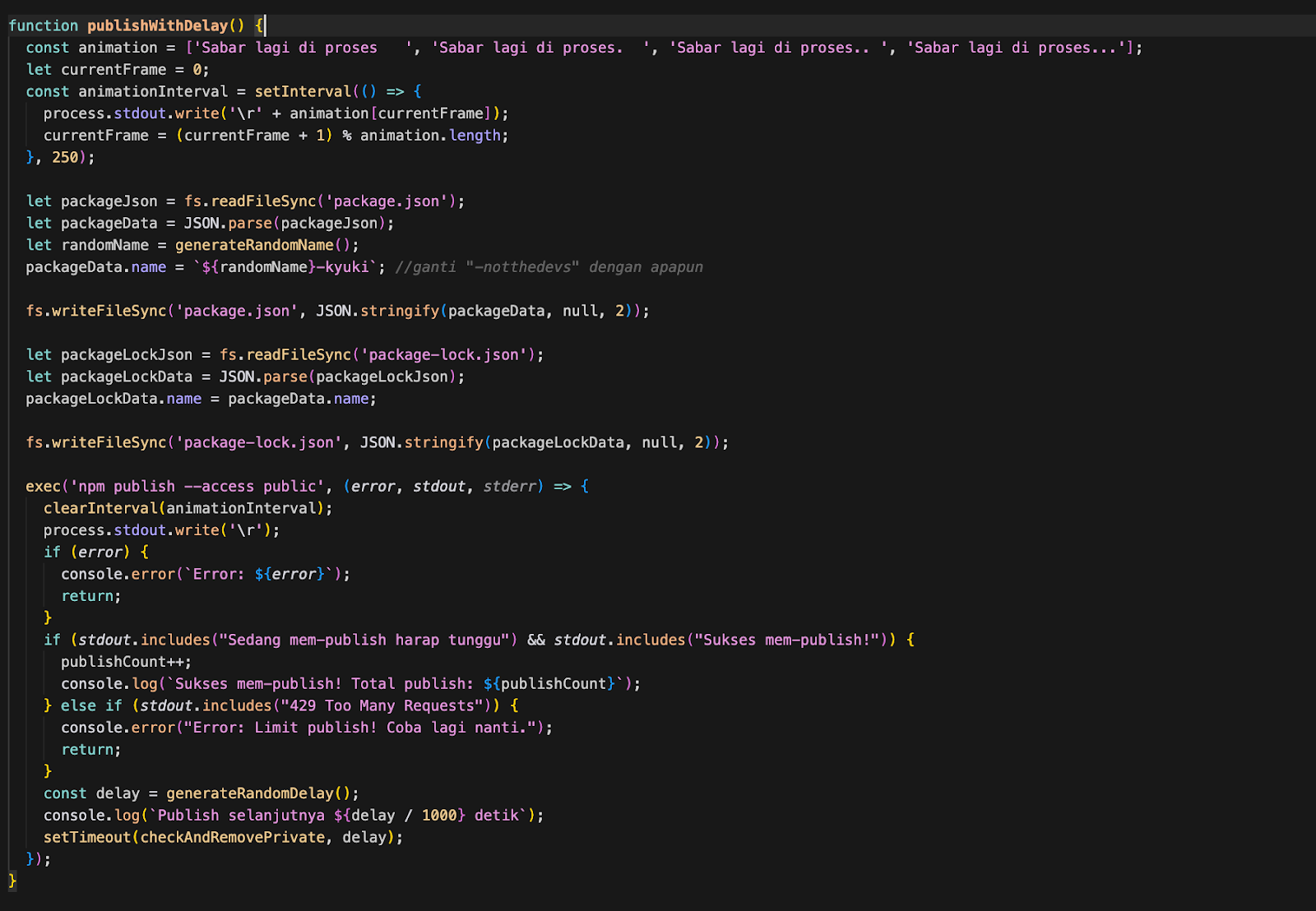

The IndonesianFoods worm gets its name from its distinctive naming scheme. The malicious script contains two internal dictionaries: one with Indonesian names (such as "andi," "budi," "cindy," and "zul") and another with Indonesian food terms (including "rendang," "sate," "bakso," and "tapai"). When the script runs, it randomly selects one name, one food term, adds a random number (1-100), and appends a suffix like "-kyuki" or "-breki."

Endor Labs researchers found evidence that these packages were part of an attack first described in April 2024, in which adversaries aim to abuse the TEA protocol for rewarding open source contributions. It is surprising that even though the attack was described a year and a half ago, most of the offending packages were kept on npm until today. In total they represent more than 1% of the entire npm ecosystem. While we did not find evidence that any of the packages or their attacker-controlled dependencies contain malicious code, we noticed that some packages have thousands of weekly downloads. This leaves an opportunity for the attackers to push a malicious commit in the future that would affect all those downloads.

Our analysis examines how the campaign operates, why it remained undetected for so long, and its implications for the JavaScript ecosystem.

Campaign Overview

The IndonesianFoods worm gets its name from a distinctive characteristic: every package uses Indonesian names and food terms in its naming scheme. Packages follow patterns like `zul-tapai9-kyuki`, `andi-rendang23-breki`, and `budi-sate73-kyuki`, where "zul," "andi," and "budi" are common Indonesian names, while "tapai," "rendang," and "sate" are Indonesian food terms. The numbers appear random, and suffixes like "-kyuki" or "-breki" remain consistent across variations.

The complete dataset, including all package names and metadata, is available in the Indonesian-Foods-Worm GitHub repository.

How the Attack Works

Each package in this campaign appears legitimate at first inspection. Opening any package reveals a standard Next.js project structure, complete with proper configuration files, legitimate dependencies (React, Next.js, and Tailwind CSS), and professional-looking documentation. This camouflage is intentional and effective.

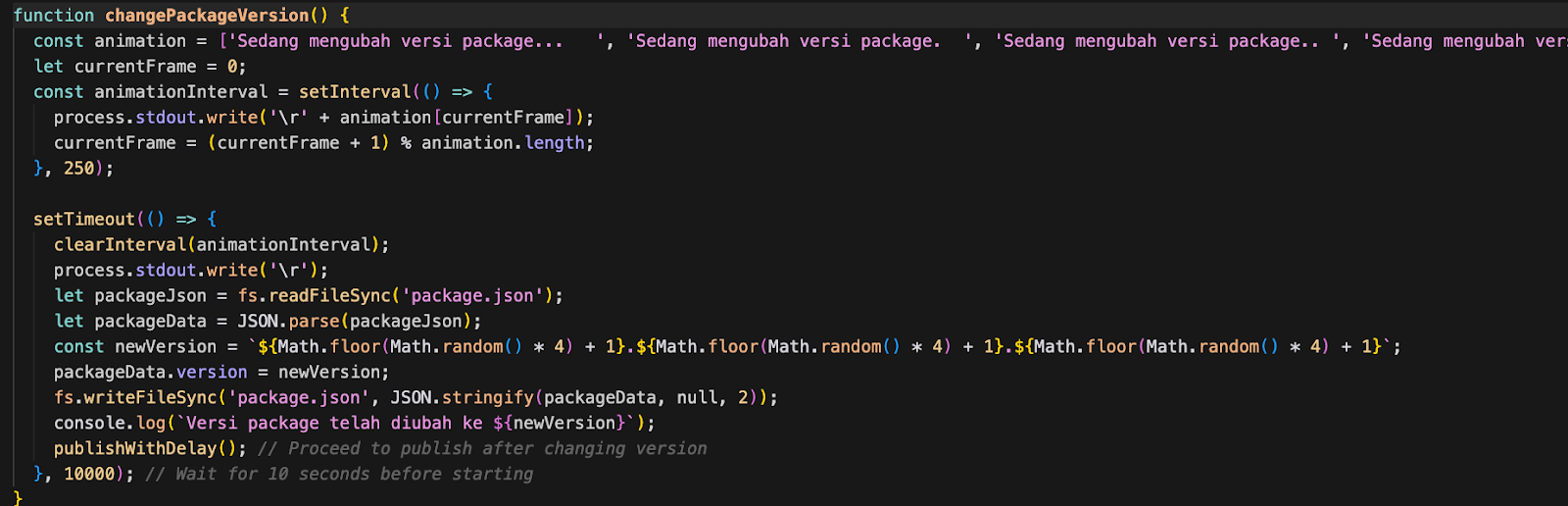

The malicious component is a script file that sits unreferenced in the package structure. Depending on the variant, this file is named either `auto.js` or `publishScript.js`. Unlike typical npm malware, this script doesn't execute automatically during installation. There are no `postinstall` hooks, no lifecycle scripts that trigger on `npm install`. The package is genuinely inert until someone manually runs the script (e.g., `node auto.js` or `node publishScript.js`).

When executed, the script performs three actions in an infinite loop:

Stage 1: Remove Privacy Protection

The script checks for `"private": true` in package.json and removes it. This flag is used by developers to prevent accidentally publishing proprietary code to public registries.

Stage 2: Randomize Version

It generates a random version number, such as "2.3.1" or "4.1.3", to bypass npm's duplicate version detection.

Stage 3: Publish to Registry

The script generates a new random package name using its internal Indonesian dictionaries, updates package.json and package-lock.json, then executes `npm publish --access public`. After a 7-second or 10-second delay, the cycle repeats.

The mathematics of this attack are concerning. A single execution publishes approximately 12 packages per minute, 720 per hour, or 17,000 per day. The existence of 43,900 packages suggests either multiple victims executed the script or the attackers ran it themselves to flood the registry.

The Worm Behavior: Dependency Chain Infection

What makes this campaign particularly insidious is its worm-like spreading mechanism. Analysis of the ‘package.json’ files reveals that these spam packages do not exist in isolation; they reference each other as dependencies, creating a self-replicating network.

When a user installs one of these packages, npm automatically fetches its entire dependency tree. If each spam package includes 8–10 additional spam packages as dependencies, the spread grows exponentially. Installing a single package could result in pulling in over a hundred related spam packages, rapidly multiplying registry bandwidth usage, and making cleanup much more complex, since the entire dependency chain must be removed.

The Tea Protocol Connection: Monetizing Spam with Cryptocurrency

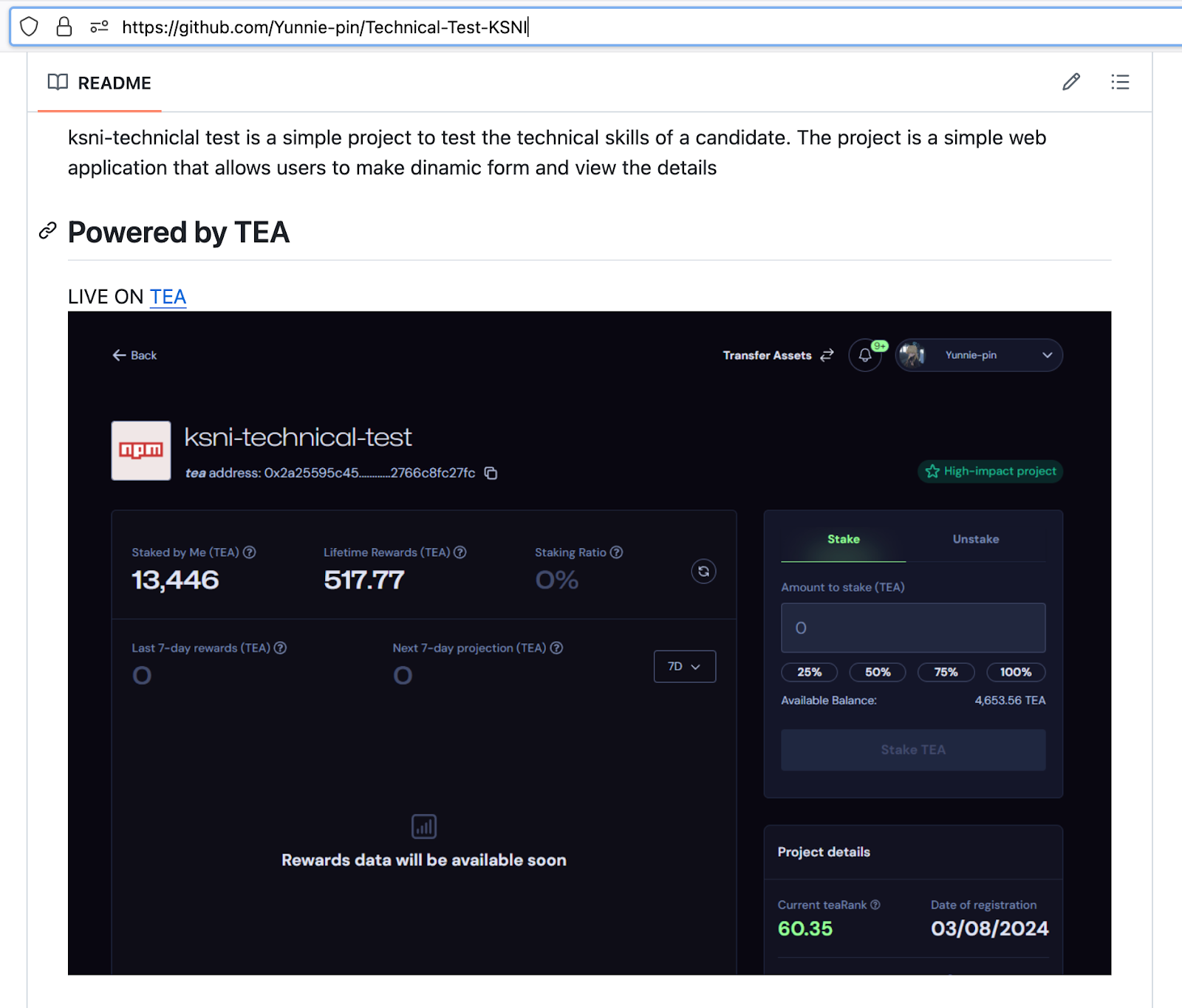

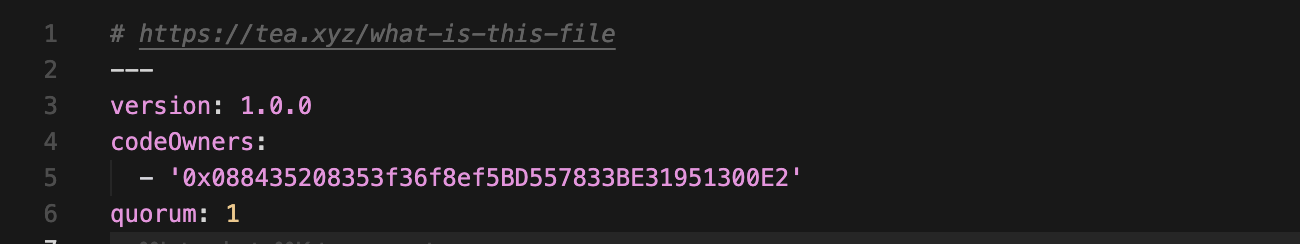

Several attacker controlled packages (arts-dao, gula-dao, kellymanteasproject, ksni-technical-test, seblak88, seblakkuah, sukajeruk23, yunnie-dao) include a tea.yaml file like this one in which several TEA accounts are listed. We believe that this is an attempt by the attackers to monetize this attack via tokens on a blockchain meant for rewarding OSS contributions.

Moreover, at least one of the maintainers of those packages has an associated LinkedIn profile and appears to be an Indonesian software engineer, which explains the regional-specificity of the campaign.

By embedding “tea.yaml" files across thousands of spam packages and interlinking them through circular dependencies, the attackers inflated their “impact scores” and claimed TEA token rewards for artificial ecosystem value. Notably, one of the package READMEs even boasts about these earnings, reinforcing the financial motive behind the campaign. At least one of the maintainers also appears to be an Indonesian software engineer, aligning with the regional nature of this large-scale operation.

Different variants

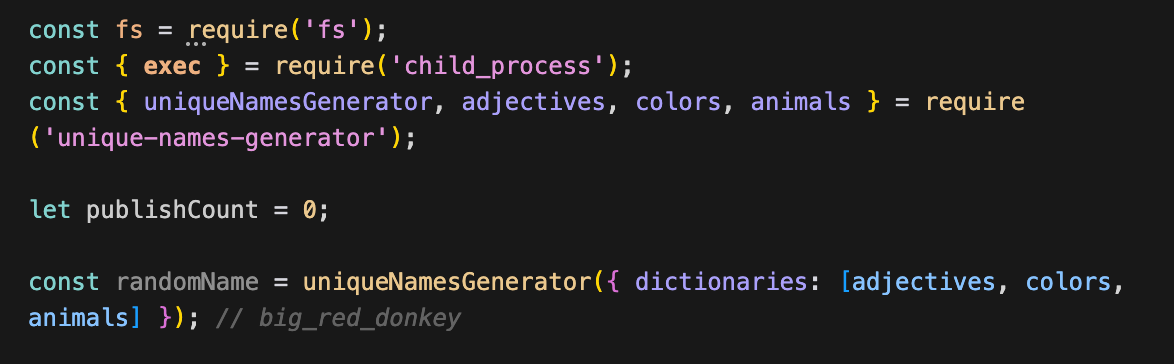

Interestingly, some variants use different name generation strategies. The example above includes “unique-names-generator”, a legitimate npm package that's actually used by the payload script to generate package names like "able_crocodile" or "big_red_donkey" instead of the Indonesian food pattern. This shows the campaign has multiple versions:

- Variant A: Indonesian names + foods (zul-tapai9-kyuki)

- Variant B: Random English words via unique-names-generator (able_crocodile-notthedevs)

Why It Went Undetected

The campaign's success in evading detection for over two years highlights significant gaps in current security approaches. Modern security scanners excel at catching packages that execute malicious code during installation. They monitor lifecycle hooks, detect suspicious system calls, and flag known malware patterns to trigger alerts automatically. In this case, they found nothing because there was nothing to find at the time of installation. Each contained legitimate dependencies, proper project structure, and standard Next.js configurations. To automated systems, these appeared as slightly unusual but fundamentally normal web development templates. The auto.js file, being unreferenced by any code, would be classified as unused dead code and ignored.

When you install one of these packages, no malicious activity occurs. The package downloads, dependencies install, and files sit dormant in node_modules. Every security scan during installation would correctly report the package as safe because it is safe at that moment. The threat only emerges if someone manually executes the payload script (auto.js or publishScript.js), which falls outside the scope of installation-time security tools.

Regarding the unlawful monetization via TEA tokens, while the abuse was described in April-August 2025, until now no one has made an effort to analyze and take down packages that aim to abuse this OSS reward mechanism. We believe security scanners should aim to understand the use of tea.yaml files and their relation to downstream dependencies and attack-controlled wallets.

What Makes This Campaign Significant

The IndonesianFoods campaign is interesting because it demonstrates that spam packages representing 1% of the ecosystem could survive for more than two years on npm. Even though the abuse of TEA tokens was well documented in 2024, nobody took the time to flag all the packages exploiting this OSS reward mechanism. The sheer number of packages flagged in the current campaign shows that security scanners must analyze these signals in the future.

At least eleven accounts (with more being discovered) operating in coordination over a two-year period suggest organized actors with sustained resources. The campaign appears to have evolved through multiple phases: initial registry spam, followed by the addition of Tea Protocol integration (tea.yaml files with Ethereum wallet addresses) to monetize the existing package network through cryptocurrency rewards. This wasn't a single planned attack, it's spammers discovering and exploiting multiple revenue streams over time.

Practical Response

If you're responsible for your organization's npm security, here's what you should do.

- Immediate Verification

Check your dependencies against the eleven compromised accounts. Look for anything published by voinza, yunina, noirdnv, veyla, vndra, vayza, bipyruss, sernaam.b.y, jarwok, doaortu, or rudiox. Cross-reference your installed packages with the complete list in the Indonesian-Foods-Worm GitHub repository. The probability of exposure is low, but verification takes minutes. Nonetheless, we see that some of the packages added as dependencies in this attack have more than 2,000 weekly downloads: https://www.npmjs.com/package/ksni-technical-test.

- Access Control Audit

Confirm that npm publish permissions are restricted to CI/CD systems and authorized maintainers. Ensure developers cannot accidentally publish from local machines. This control prevents the secondary risk of code disclosure if someone the malicious script.

- For Registry Operators

npm needs tighter rate limiting on package publishers, automated pattern detection for bulk spam campaigns, and potentially stricter account verification for high-volume publishers. The fact that eleven accounts published 43,900 spam packages over a two-year period without triggering automated alerts suggests defensive gaps.

Broader Implications

This campaign demonstrates that volume, persistence, and strategic thinking can succeed where technical sophistication alone might fail. The npm ecosystem operates on a foundation of trust. Millions of developers run `npm install` daily, implicitly trusting that downloaded packages won't cause harm. This trust is usually warranted; the vast majority of npm packages are legitimate. But trust is fragile, and campaigns of this scale erode it. Developers become more skeptical, security teams add friction, and the ecosystem's efficiency degrades.

The IndonesianFoods worm also signals an evolution in attack strategies. Traditional supply chain attacks focused on compromising high-profile packages for maximum immediate impact. This campaign took the opposite approach: publish thousands of low-profile packages and let probability work in your favor and. It's a volume game where even unlikely events become inevitable given enough opportunities.

Additionally, attackers monetized the fake dependencies in their packages as a way to boost their OSS reputation, and potentially, earn TEA tokens. We recommend the TEA project take a proactive stance in tracking and taking down offending user accounts and wallets to discourage abuse in the future. In particular, the TEA accounts involved in this campaign should be deactivated immediately to prevent attackers from earning more undeserved money.

The security community's response is already underway. Databases like OSV.dev are being updated with the campaign's indicators. Security tools are incorporating detection capabilities. Organizations are scanning their dependencies and updating blocklists. But while reactive measures address this specific campaign, the underlying vulnerability remains.

Conclusion

The IndonesianFoods worm represents a significant coordinated spam campaign in the npm ecosystem. While individual packages require manual execution to activate their payload, the scale (over 43,000 packages and counting), coordination (multiple accounts still being discovered), monetization via TEA tokens, and duration (online for over two years) make this a notable supply chain event.

The npm ecosystem will recover from this. Packages are being removed, databases are being updated, and defenses are being strengthened. But similar campaigns are inevitable. The important question is: will the lessons learned from this one make the next detection faster and the impact smaller?

Credits

- Initial discovery and comprehensive documentation by Paul McCarty at SourceCodeRed

Detect and block malware

What's next?

When you're ready to take the next step in securing your software supply chain, here are 3 ways Endor Labs can help:

.jpg)

.avif)